Te Mana o Te Wai – the mana of the water

The Motueka Catchment Collective’s vision is “The Motueka River/Awa is vibrant with life and supports the wellbeing and health of the connected environment and communities”.

The Motueka Catchment Collective’s vision is “The Motueka River/Awa is vibrant with life and supports the wellbeing and health of the connected environment and communities”.

This represents community sentiment reflected in MCC’s 2023 community survey for there to be a higher valuing of our rivers and a greater recognition for cultural and spiritual values. MCC’s Living River Thematic Group was also set up following the identification of a community priority around letting our rivers flow more naturally and flourish.

This sentiment was reconfirmed at MCC’s July Living River event which explored indigenous perspectives towards freshwater. Those who attended were asked what vision they had for the Motueka River. Responses included that we need to put the awa first, to grow the love for our rivers, return our rivers to their natural state, and promote a deeper level of conservation of our rivers including iwi values.

This article explores the broader context and framework being put in place for Aotearoa’s freshwater which recognises more strongly the mana of water, and of the place of Māori as key decision makers about the management of our freshwater systems.

What is Te Mana o Te Wai?

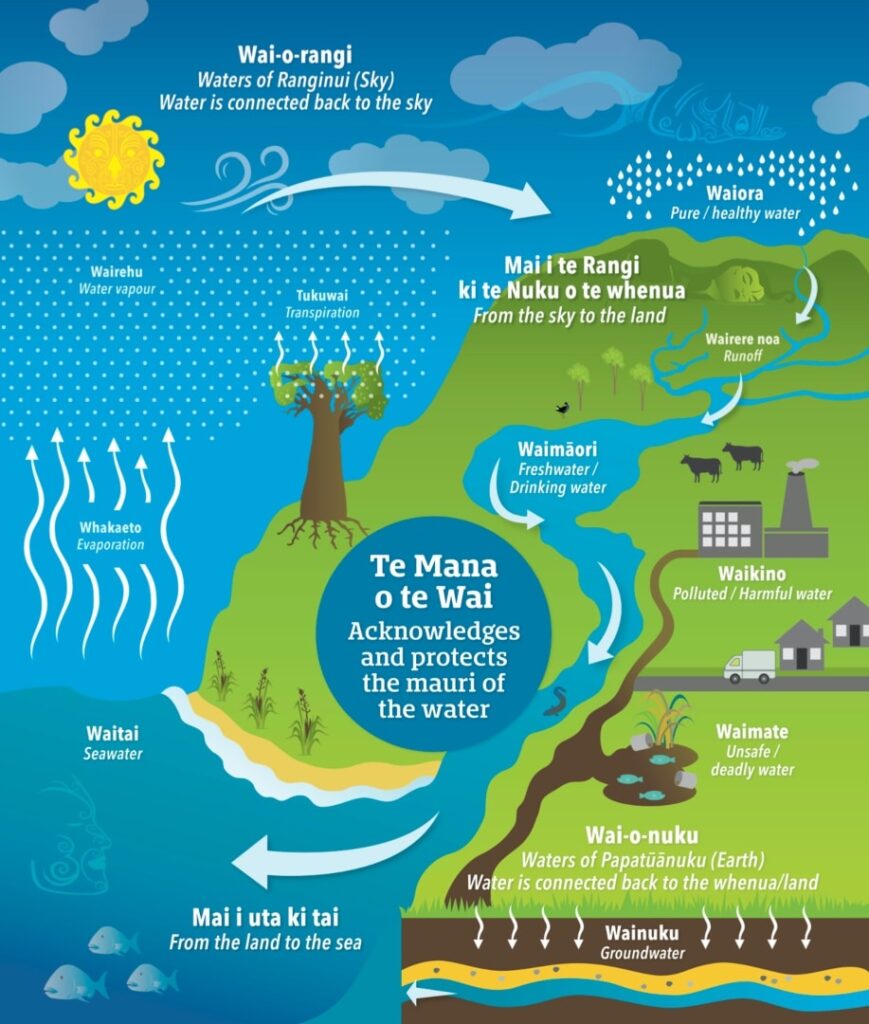

Te Mana o Te Wai is an approach focused on assuring water for human consumption as well as restoring and preserving the balance between the water, the wider environment, and the community.

It places the highest importance on the life supporting capacity of water (see a fuller explanation of this below). First, we need to protect the health and well-being of freshwater ecosystems for their own sake, then provide for people’s needs, before enabling other uses of water. This is a world leading approach.

Te Mana o te Wai adopts a Te Ao Māori framework and is centred around iwi and hapū being actively involved and engaged in decisions.

https://www.aquaworks.co.nz/te-mana-o-te-wai/

What principles does Te Mana o Te Wai have?

Te Mana o Te Wai has six principles. The first three relate to tangata whenua, the second three to the government and other citizens of New Zealand:

- Mana whakahaere, Kaitiakitanga, and Manaakitanga: the power, authority, obligations and process of tangata whenua to make decisions and show respect, generosity and care in a way that maintains, protects, and sustains the health and well-being of, and their relationship with, freshwater for the benefit of present and future generations.

- Governance, stewardship and care and respect: the responsibility of those with authority for making decisions about freshwater, and the obligations of all New Zealanders to act a way that prioritises the health and well-being of freshwater now and into the future, and with care for freshwater.

What is the life force of water?

Wai (water) is essential for life. For the wild animals that live in the streams, wetlands and rivers. And for people who need it for drinking, eating and cleaning.

Rivers and streams sustain more than just life. For generations the people living around a water body have relied on it for food, spirituality, to swim, and to live well. When the water is gone, the way of life goes too.

Most people in New Zealand deeply care about the health of the rivers and have a special connection with fresh water. Most of us know streams, rivers, and watery places that are important to us. We visit places of such pure water as the Riuwaka Resurgence, Rotomairewhenua, the Blue Lake or Te Waikoropupu Springs to refresh our spirits.

Te Puna o Riuwaka. Photo courtesy of Dana Carter

The concept of ‘te mana o te wai’ recognises the power and significance of water to all life, its life force, the integrity of a river. Te mana o te wai recognises and aims to protect the mauri, the life force of water. It recognises the river or spring has a right to be, for its own sake.

In te Ao Māori, a river is often regarded as atua or tupuna, and oftentimes given personhood. In a pepeha, by which Māori introduce themselves, rivers – and mountains, ocean, creatures and the land itself – are identifying parts of their whakapapa or lineage. These are reciprocal relationships of mutual care and guardianship.

This Māori worldview can lead us to treat the land and water with the respect we give our family. As a concept te mana o te wai signifies the respect we should give the water that gives us life.

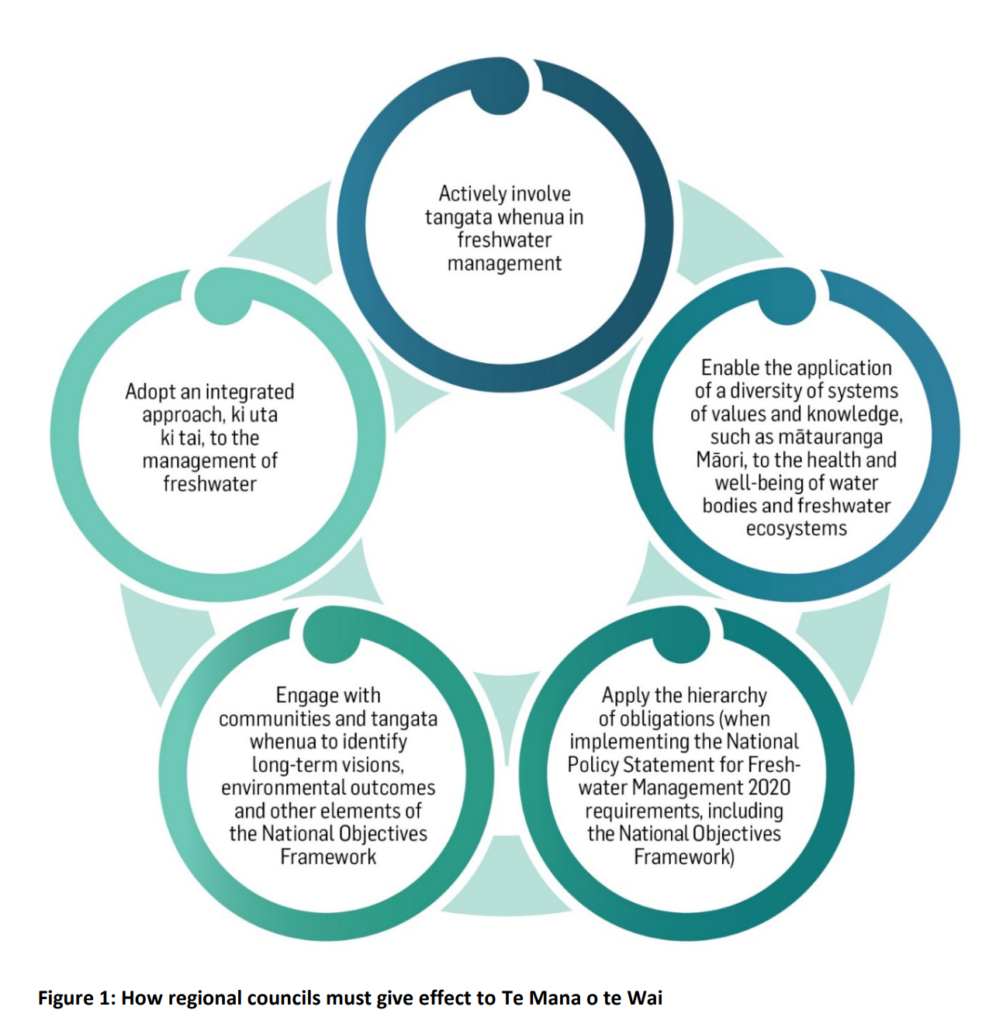

How is Te Mana o Te Wai given effect to?

The requirement to give effect to Te Mana o te Wai is set nationally, but it will be applied locally. Councils, through active involvement with tangata whenua, and engagement and discussion with communities, will determine how to apply Te Mana o te Wai locally, based on the visions and tikanga of its people.

You can read here what progress has been made – https://shape.tasman.govt.nz/mountains-to-the-sea/healthy-water-healthy-communities-te-mana-o-te-wai

How is Te Mana o Te Wai relevant to the Motueka catchment?

Council is working in partnership with eight iwi from across Te Tauihu/the Top of the South to develop a local understanding of how we can apply Te Mana o te Wai in our region. This case study report has been prepared for the iwi of Te Tauihu https://ngatitama.nz/temanaotewai/ the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge: Enacting Te Mana o te Wai through Mātauranga Māori.

Six iwi were involved in its preparation including Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō, Ngāti Koata, Ngāti Kuia, Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Rārua, Ngāti Tama Ki Te Waipounamu and Te Ātiawa Manawhenua Ki Te Tau Ihu. Representatives from Rangitāne o Wairau and Ngāti Toa Rangatira maintained a watching brief through the project. A series of iwi led hui were carried out during 2021 then a working group of Pou Taiao representatives was established to work together to prepare the report.

Te Tauihu has 16 major river catchments linking the inland mountains to the coast. The major ancestral awa include ko Wairau, ko Te Hoiere / Pelorus, ko Mahitahi / Maitai, ko Waimeha / Waimea, ko Motueka, ko Riuwaka / Riwaka, ko Tākaka and ko Aorere.

Extracts from the report which mention the significance of the awa and freshwater systems of the Motueka Catchment to iwi now and in the past include:

Te Puna o Riuwaka also has special mana as the source of wai ora or the waters of life and is a taonga for Ngāti Rārua. The pools have for generations been a place for whānau to come for spiritual sustenance, cleansing and healing, and the whole area associated with the Riuwaka awa is one of the most sacred sites in Te Tai o Aorere. The Riuwaka is also associated with Tāmati Parana, a revered tohunga who utilised the healing powers of the river stones. These stones continue to be of great significance today for healing purposes.

“… the Motueka River, which was originally a braided river system with a flood plain, rather than the single channel it is now. Harakeke and raupo were common in the lowland wetlands behind the beach ridges. Tradition describes the Motueka flood plain as an extensive and bountiful mahinga kai, replenished and fertilised by floods and supporting a wide variety of resources and cultivations.

Wetlands such as the Motueka, the Moutere Valley, and the Para Swamp in the Waitohi Valley, were important mahinga kai for ngā tupuna, providing birds, fish and eels, as well as harakeke and raupo. The wetlands are areas where customary harvesting traditions and practices have been taught from one generation to the next.

These extracts describe the damage caused to awa in the Motueka catchment during the time of European settlement:

…in the late 1880s, the local government altered the course of the [Motueka] river and [associated smaller streams] dried up… Te Atiawa lost both their fisheries and their fresh water for their domestic use… Change continued in the twentieth century. The Motueka and Riwaka rivers still run to the sea… but their wairua and water quality have been compromised.

Waterways, tributaries, creeks, wetlands and swamps have for the best part been drained of their valuable resources and replaced with culverts, water pump stations, cattle fords and dams.

And the following are specific references in the report to what is needed in relation to the Motueka freshwater system:

Managing increasing demand for irrigation from groundwater in the Upper Motueka Valley requires knowledge of how these alluvial aquifers interact with the Motueka and tributary rivers, and how groundwater pumping indirectly impacts aquatic ecology

More information is needed on gravel transport mechanisms in Motueka rivers, especially during floods, to understand the decline in riverbed levels, and how to best manage gravel extraction from rivers.

This is the Tasman District Council’s contribution to this study – Volume-II-Te-Mana-o-Te-Wai-Te-Tauihu-Councils-Reports-FINAL-050821_DISCLAIMER.pdf (ngatitama.nz). This report documents the councils freshwater management framework and process of strengthening this structure, improving information, engaging the community, iwi, and addressing key issues in catchments, and re-establishing the hierarcy for managment recognising Te Mana o te Wai.

As it says on TDC’s website:

In alignment with the NPS-FM, the Land and Freshwater Plan (LFPC) will adopt an integrated management approach and recognise the interconnectedness of the whole environment – from the mountains to the sea, the connections between waterbodies and between land and water, and the relationships people have with their local places.

See this page for an update of where the council is at with this process – https://shape.tasman.govt.nz/mountains-to-the-sea. It is expected that the draft plan will be available for comment around the end of 2024.